Timeless Masterpieces: A Journey Through Art and History, art is much more than simple images or decoration: it is a universal language capable of telling deep stories and evoking intense emotions.

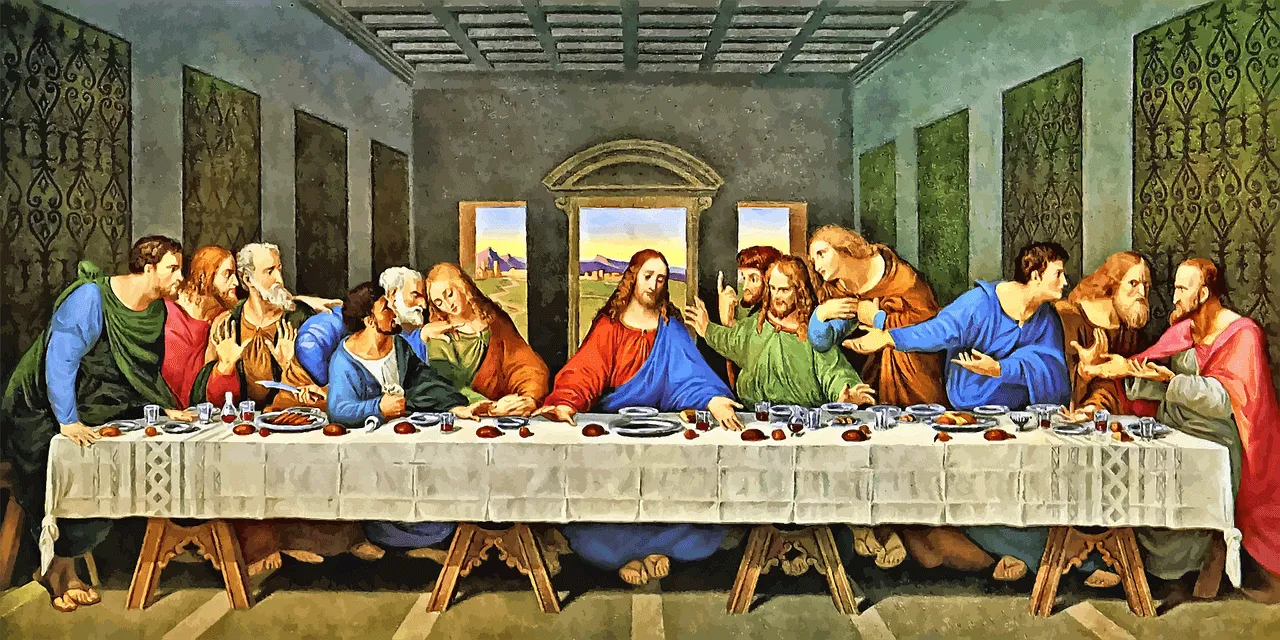

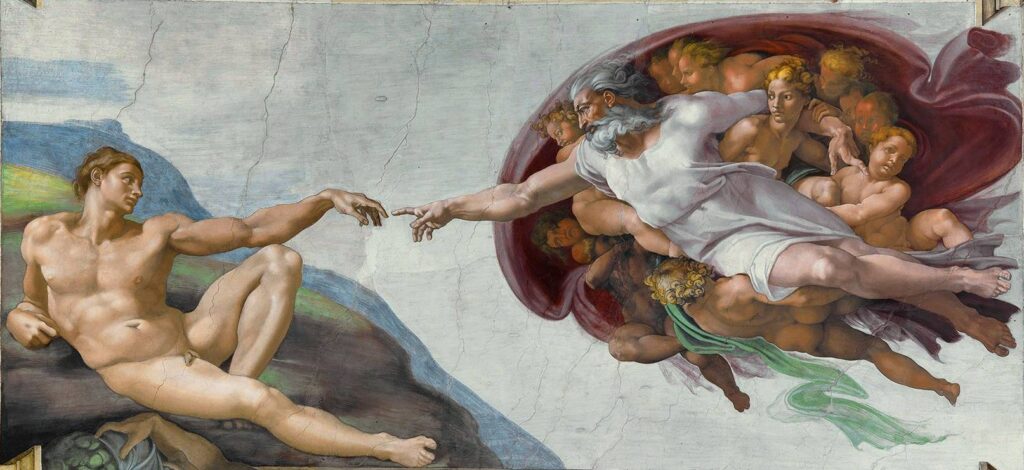

Throughout the centuries, great masters have shaped this language with unique visions, creating works that still speak directly to the soul of those who observe them.

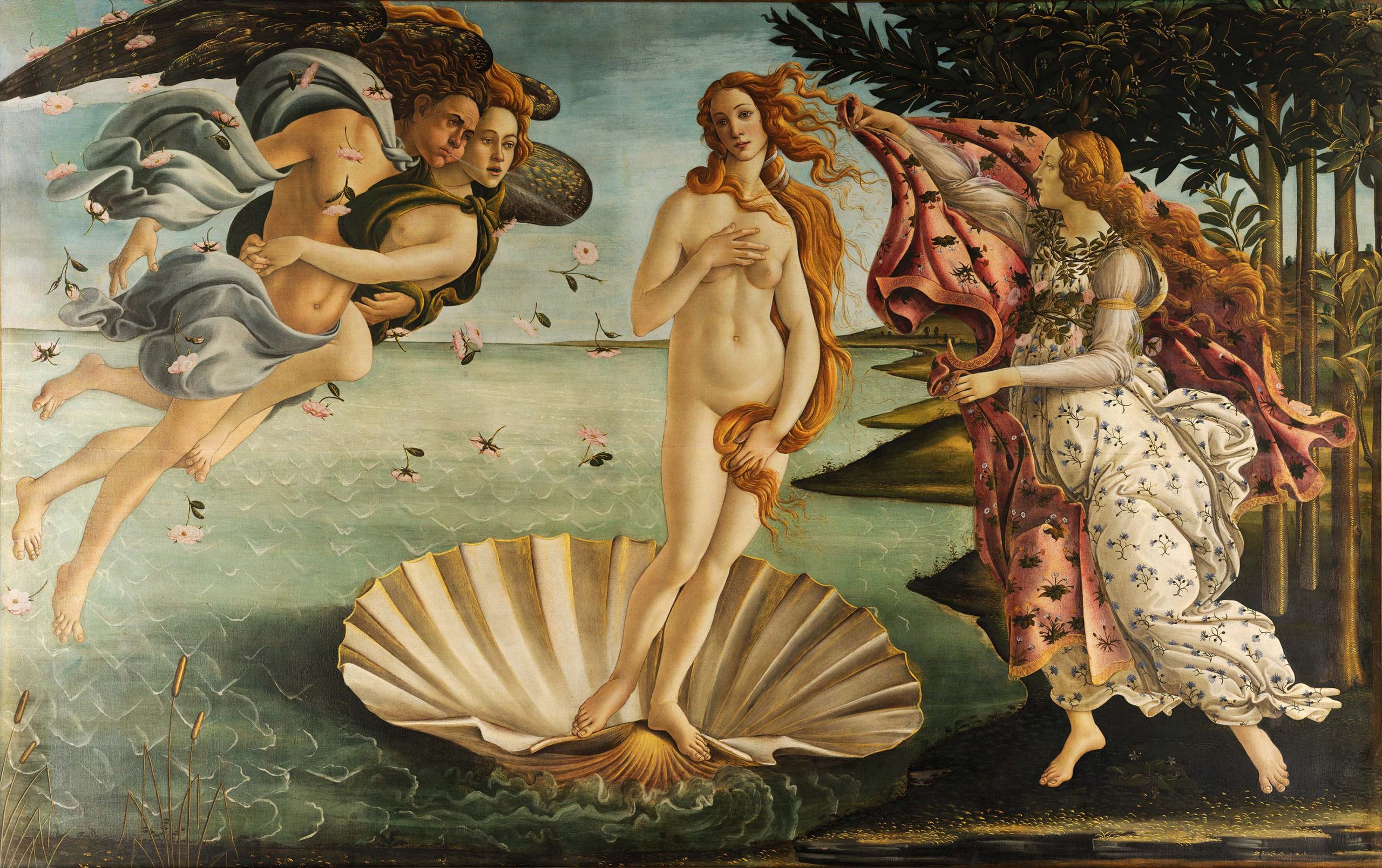

In this journey, we will explore some of the most famous masterpieces in the world from The Birth of Venus to Guernica touching on themes of beauty, pain, revolution, and hope.

Each artwork holds within it a fragment of history, a testimony of different eras and cultures, and a message that transcends time.

This collection aims to be an invitation to immerse oneself in the world of art, to discover the details, symbols, and emotions that make each painting a treasure to cherish.

An experience that not only enriches knowledge but also nourishes the spirit, reminding us how art is a powerful tool for communication and reflection.